Introduction

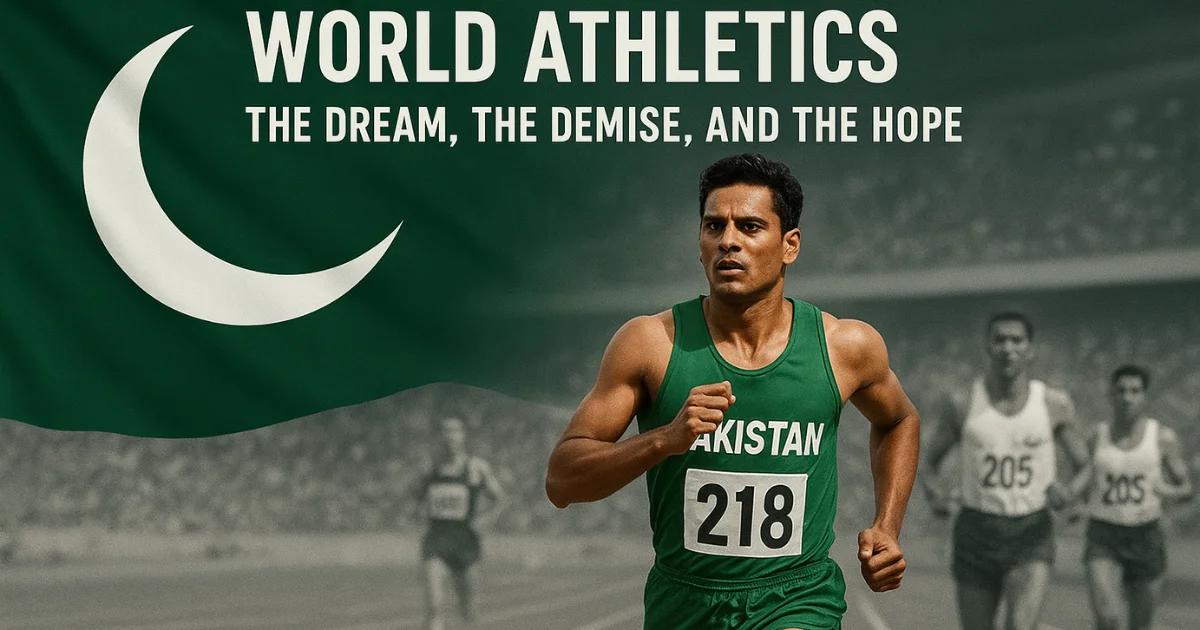

Athletics — the sprint, the jump, the throw, the simple measuring of human speed, strength and endurance — has long been a clear mirror of a country’s sporting ecosystem. For Pakistan, athletics has been a story told in three acts: an early dream of regional prominence and bright personalities, a long period of decline and neglect, and, in recent years, a rekindling of hope built around individual grit and a few breakthrough performances on the global stage. This is the story of how Pakistan once competed for medals in Asia and the Commonwealth, how institutional failures dimmed that light, and how a new generation — led by singular talents — is rewriting the narrative in world athletics, the Asian Games and the Commonwealth Games.

The Dream: early promise and continental success (1948–1970s)

In the years following independence Pakistan inherited a sporting culture that, while limited in resources, contained pockets of genuine talent. The Athletics Federation took shape early on and athletes began to appear on continental lists. In the 1950s and 1960s especially, Pakistani track and field athletes won medals at Asian and Commonwealth levels and produced names that were celebrated at home.

One of the earliest and most resonant figures was Abdul Khaliq, who emerged in the 1950s as Pakistan’s premier sprinter and as one of Asia’s fastest men of the era. He won major continental honours and set sprint records that established Pakistan on the athletics map in Asia. His era coincided with Pakistan’s relatively strong showings at the Asian Games in the 1950s, where the country claimed a number of athletics medals and ranked among the stronger athletic contingents in the region.

Another pillar of that early era was Ghulam Raziq, a specialist hurdler whose continental and Commonwealth Games medals contributed to Pakistan’s medal hauls in multi-sport competitions. In the late 1950s and early 1960s Pakistan not only sent athletes to major events but also returned with podium finishes in athletics — evidence that the dream of a competitive athletics programme was real and attainable.

The 1950s and 1960s were the decades during which Pakistan’s athletics identity formed: relatively small teams but with athletes capable of competing for — and winning — medals in Asia and the Commonwealth. National pride in these athletes reflected a broader optimism: that Pakistan could produce specialists who rivalled the best in the region.

The Demise: neglect, lost momentum and widening gaps (1980s–2000s)

The dream did not collapse because the talent disappeared. Rather, the structural supports around athletics did. Over time political interference, weak governance in sports institutions, chronic under-funding, and the failure to maintain or build modern training facilities left athletics to flounder.

While other sports or countries invested in science-based coaching, youth development pathways and international exposure, Pakistan’s athletics ecosystem did not receive sustained, strategic attention. Stadiums and tracks aged without renewal; opportunities for coaches to learn modern methods dwindled; and sponsorship and media interest moved to sports with larger commercial returns. The result was predictable: athletes had fewer opportunities to reach world standards, competition exposure became patchy, and the pipeline of emerging talent narrowed. This erosion was visible in declining results at the Asian level and the near disappearance of Pakistan from serious contention in global championships.

Concurrently, the world of athletics itself surged ahead: improvements in coaching methodology, nutrition, sports medicine and year-round competition sharpened the performance gap between countries with strong athletics programmes and those left behind. Pakistan’s athletes increasingly found themselves competing symbolically at major events rather than as legitimate medal contenders. The flame of the golden era had not been extinguished entirely, but it was dimmed by systemic failures.

Pakistan and the World Athletics Championships: absence and first steps

The World Athletics Championships — the global meet outside the Olympics where world-class athletes test themselves against the best — has long served as the clearest barometer of a nation’s worldwide standing in track and field. For decades Pakistan’s presence at global athletics championships was minimal, with athletes rarely progressing beyond qualifying rounds. That absence reflected the deeper problems: lack of preparatory competitions, inadequate coaching, and insufficient exposure to elite meets.

In the 21st century, and notably in the 2010s, Pakistani athletes started to show up more often in World Championships and other international competitions. in first, they were just participants, but after a few great performances, they became competitors who could make it to the finals. These first steps onto the world arena were very important because they showed that Pakistani sportsmen could compete with athletes from other countries if they had the correct mix of talent and training.

The importance of the World Championships for Pakistan is twofold. First, the Championships provide top-level competition that accelerates an athlete’s development — competing in a world final is a different education than regional meets. Second, success at the World Championships brings visibility that can catalyse investment and national interest. When Pakistani athletes began to place or reach finals at world level it signalled the possibility of moving from representation to genuine competition.

Commonwealth Games and the Asian Games: where Pakistan mattered

Historically, Pakistan’s greatest impact in athletics came at the Asian Games and the Commonwealth Games. At those events Pakistan found the competitive environment best suited to its level of development at the time: regional rivalries, familiar competition circuits and shorter travel demands. Pakistan won some of its most important athletics medals in those forums, and the country’s sporting prestige at home was often tied to performances at these two multi-sport games.

The Asian Games of the 1950s and 1960s saw Pakistan among the athletic medal-winning nations. For example, the 1958 Asian Games were particularly fruitful when Pakistani athletes returned from Tokyo with multiple athletics medals across sprints, hurdles and middle-distance events; those medals affirmed Pakistan as an athletics force in Asia at that time.

The Commonwealth Games, too, were a platform where Pakistan found success. The 1962 Commonwealth Games stand out as one of Pakistan’s most successful editions — Pakistan finished highly in the overall standings across sports and took home athletics medals that remain important in the country’s sporting memory. Athletes from that era demonstrated that Pakistan could produce Commonwealth-level champions, a reality that inspired generations to come.

For decades these two events formed the backbone of Pakistan’s competitive calendar — the places where athletic dreams were most likely to be realized. Even when global results proved elusive, regional and Commonwealth success provided a continuing sense of identity and achievement in Pakistan’s athletic narrative.

The Hope: breakthrough individuals, changing perceptions

The resurgence of Pakistan in modern athletics has been driven not by systemic overhaul but by extraordinary individuals whose talent, resilience and results have forced attention back onto the sport. The most prominent contemporary example is the javelin thrower whose achievements have changed the conversation about Pakistan on the world athletics stage.

In recent years a Pakistani javelin thrower rose through limited local resources to claim top finishes at major championships: a Commonwealth Games gold and games record, competitive finals at World Championships and landmark performances at the Olympics and international circuit meets. Those performances marked Pakistan’s arrival as a country capable of producing world-class specialists and, crucially, created momentum for renewed public and institutional interest.

This athlete’s Commonwealth Games gold in 2022 — the country’s first athletics gold at the Commonwealth level in decades — revived memories of the early eras and showed how a single discipline might lift an entire sport’s profile. Following that, podium finishes at World Championships and Olympic finals turned symbolic participation into competitive success on the highest stage, helping to alter the narrative from mere representation to genuine contention.

The accomplishments in question have a number of significant impacts. First, they show that Pakistani athletes can reach world-class levels if they get the right coaching, have the chance to compete in other countries, and stay focused, even if they start their athletic careers in less than ideal conditions. The second benefit is that the achievement gets people talking, and when people talk about it, it opens up the possibility of getting sponsors, better training possibilities in other nations, and a stronger case for investing in training facilities, gyms, and coaching courses in the US. Lastly, the psychological boost for younger athletes can’t be overstated: when someone from their country makes it to the World Championship final or wins a Commonwealth gold, it changes what they think is achievable.

Why infrastructure, coaching and pathways matter

Individual miracles can inspire, but systemic progress requires structures. Pakistan’s path back to sustained athletics success will need attention in several interlocking areas:

1. Facilities – Synthetic tracks, access to modern throwing circles and equipment, indoor training facilities for the off-season, and well-maintained stadiums across provinces create an atmosphere where potential may be developed rather than discovered by chance. This environment is essential for the development of athletes.

2. Coaching and sports science—Along with skill, current training, recovery routines, biomechanics, and nutrition are all just as important.

3. Talent identification and grassroots school programs—athletics needs a lot of people to be successful. Competitions at the school and district levels that lead to provincial and national teams assist uncover long-term talent and train athletes who improve on set schedules.

4. Ongoing funding and exposure to competition—It’s important to regularly compete on the Asian circuit, the Diamond League, and other international meetings. These contests help athletes learn how to deal with stress and get better by putting them through the same things over and over.

5. Institutional governance — Transparent, professional leadership in athletics federations ensures funding is allocated strategically and that programmes continue across election cycles and political changes.

If Pakistan can channel the momentum of recent breakthroughs into systemic investment, the nation can move from occasional brilliance to steady competitiveness in selected disciplines — particularly throws and technical events where individual coaching can produce faster gains.

Reframing national sporting identity

The success of an individual on the world stage forces a rethink of what a country’s sporting identity can be. For Pakistan, long dominated internationally by team sports achievements, major athletics breakthroughs have the power to expand public imagination: a nation that wins on the cricket pitch can also have athletes who jump, sprint and throw among the world’s best. The Commonwealth and Asian Games remain especially important in this recalibration because they are both historically resonant and practically reachable targets for the next generation.

Medals and finals at the Commonwealth and Asian levels create testimonies that young athletes, parents and administrators can point to. They make the case for athletics as a career and justify the investments — both emotional and financial — that produce the next wave of competitors.

Conclusion: from dream to revival — a path forward

Pakistan’s athletics history is not a single straight line. It began with continental dreams and stories of national heroes, moved through a long period of decline caused primarily by structural neglect, and has now entered a phase where hope is being rekindled — but not yet institutionalized.

The country’s historical significance in the Asian Games and the Commonwealth Games demonstrates that success was once possible and can be again. The recent breakthroughs on the world stage show that world-class performances are not out of reach. What remains is the hard work of converting inspiration into systems: better facilities, modern coaching, grassroots leagues and governance that treats athletics as a long-term national project rather than a sporadic priority.

If Pakistan can build on the catalytic achievements of recent champions, and if those achievements are used as the foundation of a sustained plan, the arc that began in the 1950s may well continue into a new era — one where Pakistani athletes are no longer rare finalists but expected contenders across selected athletics disciplines. That would complete the circle: the dream realized, the demise reversed, and a genuine, durable hope established for the future of athletics in Pakistan.

Frequently Asked Questions about

Q1: When did Pakistan first compete in international athletics?

Pakistan first competed in international athletics at the 1948 London Olympics, which was less than a year after the country became independent. Pakistan’s journey in world athletics began with this event, even though no medals were won.

Q2: Who is thought to be the first person to do athletics in Pakistan?

Abdul Khaliq, who was known as “The Flying Bird of Asia,” is seen as the first and most famous athlete in Pakistan. He was the best sprinter in the 1950s, won gold at the Asian Games, and set standards for future athletes.

Q3: What were Pakistan's biggest wins at the Asian Games?

Pakistan won a lot of medals in athletics at the Asian Games in the 1950s and 1960s, especially in sprints, hurdles, and field events. At that time, these medals made Pakistan one of the strongest athletic countries in Asia.

Q4: How well has Pakistan done in the Commonwealth Games?

The 1950s and 1960s were Pakistan’s best years in athletics at the Commonwealth Games. They won medals in sprints and hurdles. Pakistan recently won a historic gold medal in the javelin throw at the 2022 Commonwealth Games.

Q5: Do Pakistani athletes have any medals from the World Athletics Championships?

In a long time, Pakistan hasn’t won any medals at the World Championships. But recent results, especially in the javelin throw, show that Pakistani athletes are getting better by making it to the finals and competing at the highest level.

Q6: What made Pakistan's sports get worse after the 1970s?

The fall was due to poor facilities, a weak government, a lack of modern coaching, and a shift in the country’s attention to cricket and hockey. There wasn’t enough money spent into athletics between the 1980s and 2000s, therefore it slipped into oblivion.

Strategic Supply Chain Leader | Finance Strategist | SAP MM Expert | US Tax & Accounts Outsourcing | Driving Organizational Excellence Through Innovation

1 Comment

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Live dealer games really feel like being at a casino now! Setting up a solid account is key, like with bigbunny vip – verification builds trust & unlocks better features. Strategic play is everything! 🤩

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

**mindvault**

mindvault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+. It’s thoughtfully designed to help maintain clear thinking

**neurosharp official**

Neuro Sharp is an advanced cognitive support formula designed to help you stay mentally sharp, focused, and confident throughout your day.